Treatment for ovarian cancer usually involves surgery and chemotherapy. Sometimes, it includes radiotherapy.

Surgery

The first treatment for ovarian cancer is usually an operation called a laparotomy. In this operation a cut is made in your abdomen. This allows your doctor to find and remove as much cancer as possible.

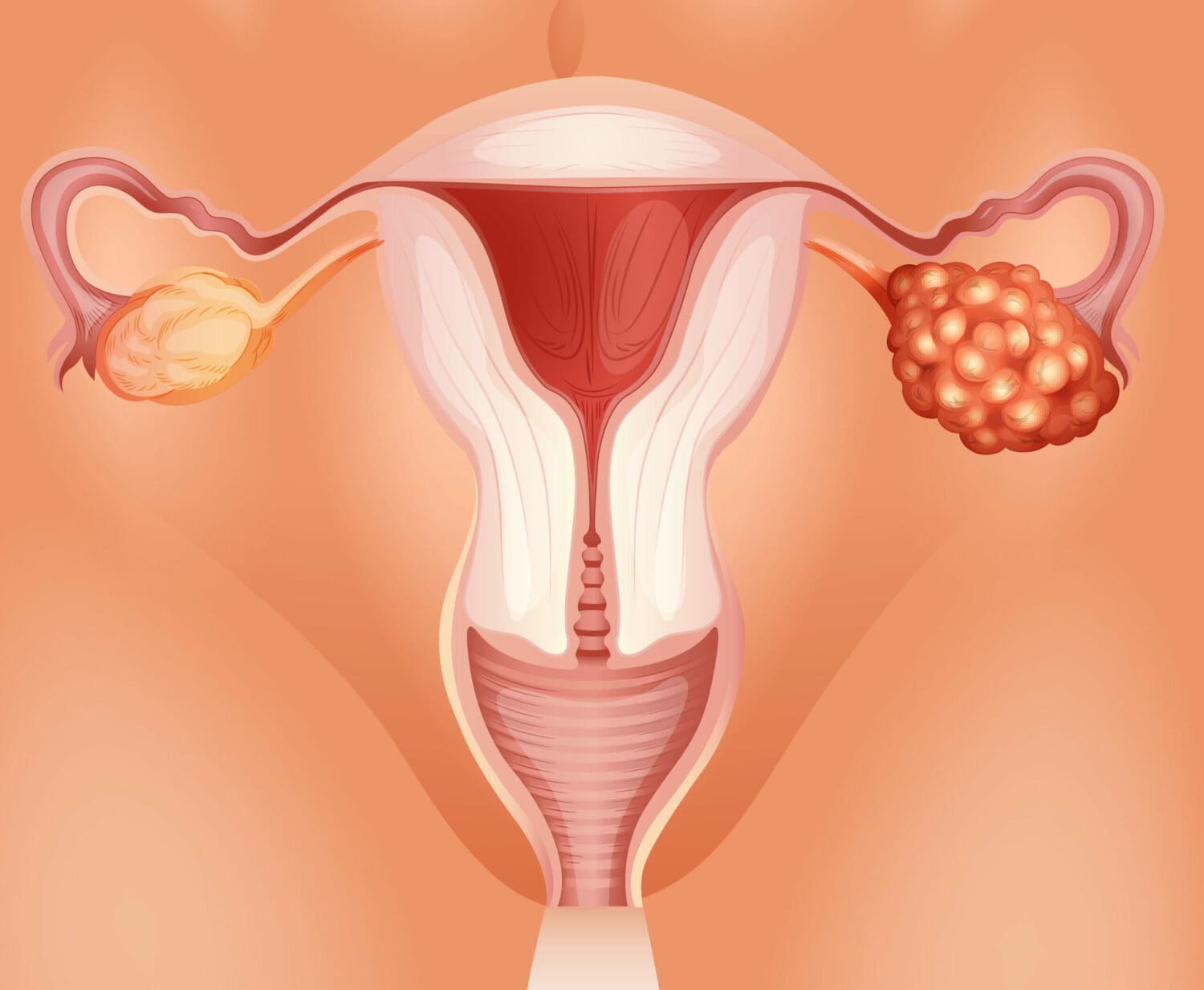

In many cases, your doctor will do a biopsy of the tumour at the beginning of the operation to make sure it is a cancer. This is called a ‘frozen section’. If cancer is confirmed, the operation will continue. The operation usually removes the ovaries and fallopian tubes, the uterus, the omentum and some of the lymph nodes in the area. The appendix may also be removed. Sometimes part of the bowel or even the bladder needs to be removed.

It may sound as if a lot of your body parts or organs are removed in the operation. However, these organs are quite small compared with everything else in your abdomen and pelvis and their removal will not leave a space.

Some women may not need extensive surgery. For instance, a young woman with an early epithelial ovarian cancer, germ cell cancer or borderline tumour may not need to have her uterus and both ovaries removed. In this case it may still be possible for her to have children.

‘Staging’ the disease

After the operation, samples of some of the organs that have been removed are sent to a laboratory for examination. The results, combined with some of your diagnosis test results, provide information about the type and extent of your cancer. This enables the doctors to ‘stage’ the disease so they can work out the best treatment for you. If the ovarian cancer you have is confined to the ovaries or very close to the ovaries, it may be called stage 1 or 2. If it has spread to other organs it may be stage 3 or 4. Knowing the stage of the disease helps your doctor discuss treatment choices with you.

After the operation

When you wake up from the operation, you will have several tubes in place. An intravenous drip will give you fluid as well as medication. You may have one or two tubes in your abdomen to drain away fluid from the operation site. You will also have a catheter in your bladder to drain away urine. As you recover after the operation, these tubes will be removed, usually within three to five days.

As with all major operations, you will feel some discomfort or pain. You will have pain relievers to control this. They may be given through an intravenous drip or through an epidural tube into your spine. This epidural pain relief is similar to that given to women during childbirth. It is best to let your nurse know when you are starting to feel uncomfortable: don’t wait until the pain becomes severe.

This operation is a major one and you may be in hospital for about one week. Before you go home, your doctor will have the results of your biopsies and will discuss further treatment with you. This will depend on the type of cancer, the extent of disease and the amount of any remaining cancer.

Further treatment, usually chemotherapy, is almost always needed for ovarian cancer.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is the treatment of cancer using anti-cancer drugs. The aim is to destroy cancer cells while causing the least possible damage to normal cells. The drugs destroy cancer cells by stopping them from growing and reproducing themselves.

Chemotherapy works best when the cancer is small and the cancer cells are actively growing. With ovarian cancer, even though most of the cancer may have been removed at the time of the operation, there may be some cancer cells left. For this reason, chemotherapy works best if it is started soon after the operation.

You will probably have chemotherapy through a vein. You will have a number of treatments, usually six, every three to four weeks over several months. It is usually a day procedure. Blood tests before each treatment will check that your body’s normal cells have had time to recover. The standard chemotherapy is a combination of drugs.

During your chemotherapy you may have other blood tests to see if the treatment is working. For example, the doctor may check for the CA 125 tumour marker.

If your cancer does not respond to one type of chemotherapy, or if your disease comes back, other drugs can be tried.

Side effects of chemotherapy

The side effects of chemotherapy differ according to the drugs used. They may include feeling off-colour and tired, and some temporary thinning or loss of hair. Your hair will grow back when treatment is completed.

Many women fear feeling sick (nausea) while having chemotherapy. Nausea can be controlled with a variety of anti-nausea medications. Tell your doctor if nausea is troubling you, so they can prescribe treatment.

‘I tried two wigs but they weren’t for me so I wore scarves. I was afraid of what other people might think but they accepted me for who I am, not what I look like.’

Some women become constipated while on chemotherapy. Ask your doctor if this is likely to happen with your treatment. Beginning laxatives early in the treatment can help. Diarrhoea is another possible side effect. This can be treated. You may be more at risk of infections. These side effects are usually temporary and measures can be taken to either prevent or reduce them.

If you are treated with paclitaxel, you may find that you have joint and muscle pain, rather like flu symptoms, for a few days after treatment. Simple pain relievers like paracetamol can help, and the symptoms usually disappear after a few days. You may also get numbness or tingling in your hands and feet after several treatments. Let your doctor know if this happens to you.

Further chemotherapy

You may need more chemotherapy if your cancer does not respond completely to your initial treatment. It may also be needed if your disease comes back some time in the future. The drugs you have will depend on what drugs you have previously had, as well as the aims of the treatment.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy (treatment using radiation) is occasionally used for women with ovarian cancer, especially if it is confined to the pelvic cavity. If radiotherapy is advised, your doctor will discuss it with you.

Complementary and alternative medicines

It’s common for people with cancer to seek out complementary and alternative treatments. Many people feel that it gives them a greater sense of control over their illness, that it’s ‘natural’ and low-risk, or that they just want to try everything that seems promising.

Complementary therapies include massage, meditation and other relaxation methods which are used along with medical treatments. Alternative therapies are unproven remedies, including some herbal and dietary remedies, which are used instead of medical treatment. Some of these have been tested scientifically and found to be not effective or even to be harmful.

Some complementary therapies are useful in helping people to cope with the challenges of having cancer and cancer treatment. However, some alternative therapies are harmful, especially if:

- you use them instead of medical treatment

- you use herbs or other remedies that make your medical treatment less effective

- you spend a lot of time and money on alternative remedies that simply don’t work.

Be aware that a lot of unproven remedies are advertised on the Internet and elsewhere without any control or regulation. Before choosing an alternative remedy, discuss it with your doctor or a cancer nurse at the Cancer Council Helpline. The US National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicines and Quackwatch are also reliable websites.

Prognosis

The prognosis for women with the less common types of ovarian cancer (for example, borderline tumours or germ cell tumours) is usually very good. For women with the more common epithelial ovarian cancer, it is not so easy to predict the outcome.

Epithelial ovarian cancer can sometimes be cured, especially for those diagnosed at an early stage. Even advanced epithelial cancers usually respond very well to initial treatment.

There is more chance that the cancer will come back (recur) if it was advanced to begin with. If the cancer does come back, although it may not be curable, further treatment (usually with chemotherapy) can sometimes shrink the cancer and help you maintain a good quality of life.

A diagnosis of cancer can make your future seem very uncertain: it may help to think of it as a chronic illness. This means that even if your cancer cannot be cured it can still be treated. You can then return to a near-normal life for periods of time.

If you would like information about your own prognosis, speak to your specialist, who is familiar with your medical history.

If any repeat of your symptoms occurs, consult your specialist, as you may need more treatment.