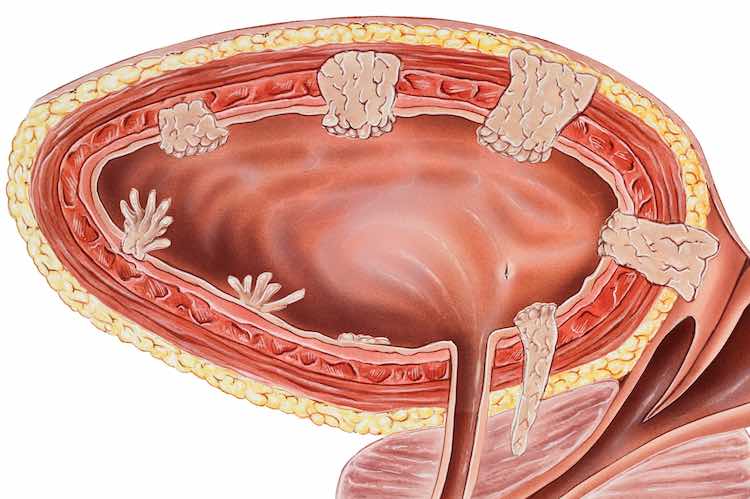

Cancer of the bladder is a tumour of the tissue lining the bladder. There are several different types, the most common being urothelial carcinoma, also called transitional cell cancer.

Cancer of the bladder occurs most frequently in people aged over 60, and is 3 to 4 times more common in men than in women. In fact it rates number four in frequency among cancers affecting men. Despite that, women don’t do as well when they have bladder cancer. The reasons aren’t clear but may have to do with later diagnosis and not always receiving the most appropriate therapy.

Bladder cancer is a cancer that is curable if caught early but has been resistant to treatment improvements over recent years. That means early detection is critical.

How do you detect bladder cancer early (signs and symptoms)?

Blood in the urine is the most common symptom of bladder cancer. The blood may be easily visible or may be ‘microscopic’ and only show up on a urine test.

Blood in the urine (haematuria) must never be ignored, no matter what your age and whether you’re a man or a woman. It must be promptly investigated by your doctor.

Some people may have symptoms of bladder irritation, such as a burning feeling when passing urine or the need to pass urine frequently or urgently. Rarely, bladder cancer causes pain in the back or lower abdomen.

These symptoms may be caused by other conditions, such as a urine infection, so getting the diagnosis right is obviously important which means seeing your doctor without delay is critical.

Who is at risk of bladder cancer?

People most at risk of bladder cancer include:

- smokers;

- people exposed at work to certain chemicals, such as used in the textile, rubber and aluminium industries;

- people with chronic cystitis (longstanding inflammation of the bladder);

- people having previous treatment for cancer involving radiotherapy to the pelvis or treatment with a chemotherapy medicine called cyclophosphamide; and

- people with schistosomiasis (a parasitic infection found in Africa, Asia and South America).

Bladder cancer diagnosis

The main test for the diagnosis of bladder cancer is a cystoscopy. This involves the insertion of a cystoscope (a long, flexible tube containing a light and a camera) into the bladder through the urethra (the tube through which urine passes out of the body). It enables the specialist to look inside the bladder and to take biopsies (small samples of tissue) for analysis.

Usually the cystoscopy will be preceded by testing the urine for cancerous cells (urine cytology) and culturing to see if there is an infection. Having an infection doesn’t mean you don’t need a cystoscopy. That’s a decision for the specialist taking into account other testing such as imaging of the urinary system, with a CT scan or an ultrasound.

How do you treat bladder cancer?

Bladder cancer treatment depends on whether the cancer is superficial (confined to the bladder lining), or invasive (has spread through the lining into the muscle of the bladder wall). Most bladder cancers are superficial at the time of diagnosis.

What surgery is done for bladder cancer?

People with non-invasive bladder cancer can have a type of surgery via cystoscopy called a transurethral resection of bladder tumour (TURBT). This type of surgery does not involve an abdominal incision and in many people it cures the cancer, although regular follow up is needed in case the cancer comes back and needs another operation.

People with more advanced cancer may need to have laparoscopic (keyhole) or open surgery, with the aim of removing all or part of the bladder (cystectomy). This is a more radical procedure which may need to divert the urine into a bag (ileal conduit). Surgeons usually do all they can to avoid this and have various techniques for doing so. In general, surgeons and hospitals doing a lot of this kind of surgery get better results.

Immunotherapy or biological treatment

Bladder cancers can often be treated by encouraging the immune system to attack them. One way of doing this involves injecting the BCG vaccine (usually used for tuberculosis, but in this case just to stimulate the immune system) into the tumour usually during a cystoscopy. There is growing evidence that new targeted anti-cancer medicines which aim at the immune system can treat bladder cancer.

Chemotherapy

Depending on how advanced the bladder cancer is, chemotherapy may be administered directly into the bladder (intravescial therapy) or though a vein into the bloodstream. Some specialists will recommend what’s called neoadjuvant therapy, where chemotherapy is given to shrink the tumour before surgery in the hope that it will reduce how radical (extensive) the operation may need to be.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy is generally used to treat invasive bladder cancer.

It is important that you ask your surgeon and cancer specialist for a consultation with a radiation expert (radiation oncologist) as sometimes this option is not utilised.

What is the outlook if you have bladder cancer?

According to the American Cancer Society:

- The 5-year relative survival rate (which is compared with similar population who don’t have the disease) for people with stage 0 bladder cancer is about 98%.

- The 5-year relative survival rate for people with stage I bladder cancer is about 88%.

- For stage II bladder cancer, the 5-year relative survival rate is about 63%.

- The 5-year relative survival rate for stage III bladder cancer is about 46%.

They also say that bladder cancer that has spread to other parts of the body is often hard to treat. Stage IV bladder cancer has a relative 5-year survival rate of about 15%. Still, there are often treatment options available for people with this stage of cancer.

Prevention

Not smoking and avoiding hazardous chemicals at work are the main ways of reducing bladder cancer risk. Early detection is the next best thing which means talking to your doctor about any unusual symptoms, especially blood in your urine.