Achalasia, also known as cardiospasm is a disorder of the oesophagus – the tube that carries food from your mouth to your stomach.

Instead of food and drink moving normally through the oesophagus when you swallow, in people with achalasia they can get stuck there, or even come back up into the mouth. Achalasia can happen at any age, but is more common in middle-aged or older adults. While there is no cure currently available, there are treatments that can help manage the symptoms.

What happens when you have achalasia?

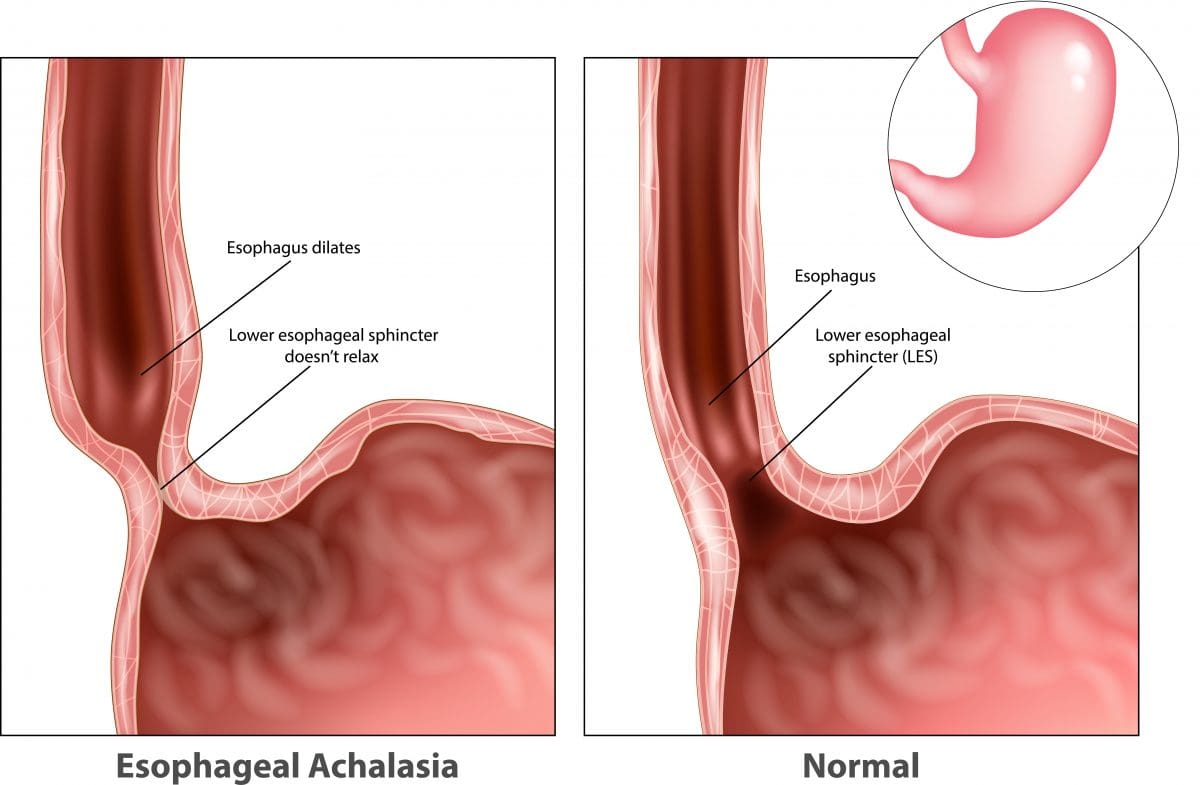

Under normal circumstances, when you swallow, food passes down the oesophagus by waves of muscle contractions and through a special valve into the stomach.

The valve – a ring of muscle called the lower oesophageal sphincter – controls the entry of food from the lower end of the oesophagus into the stomach. If you have achalasia, the nerves that control this sphincter are affected, preventing it from relaxing and allowing food to pass through.

Achalasia also affects the muscular contractions of the oesophagus (peristalsis), which normally work to propel food down towards the stomach. This is thought to be due to a malfunction of the nerves around the oesophagus.

Symptoms of achalasia

The symptoms of achalasia often start slowly and progress gradually, sometimes taking years to fully develop. They include:

- difficulty swallowing (dysphagia), which can be painful

- a lump or feeling of fullness in the throat

- chest pain

- heartburn

- regurgitation of undigested food or liquids (including when asleep)

- coughing or choking (due to regurgitation of food), which may be worse at night

- hiccups

- difficulty burping

- weight loss.

What causes achalasia?

The causes of achalasia are not well understood. Often when someone develops the disorder, there is no obvious reason why the nerves in their oesophagus no longer work properly.

Suspected possible causes of achalasia include:

- viral infections that damage the nerves of the oesophagus (this may happen earlier in life, rather than at the time of developing achalasia)

- autoimmune conditions (when the immune system attacks the body’s own cells)

- Chagas disease – an infectious disease that can destroy nerve cells.

Some people seem to be more susceptible to developing achalasia, including people with Parkinson’s disease.

Tests and diagnosis

Achalasia can be diagnosed in a number of ways. If your GP thinks you may have achalasia, you will be referred to a hospital where a specialist called a gastroenterologist may do one or more of the following diagnostic tests.

Barium swallow

The ‘barium swallow’ is a common test for achalasia. This involves drinking a thick liquid containing the chemical barium, which coats the inside of your oesophagus and stomach, making them show up on an X-ray. In people with achalasia, the test often shows that the lower part of the oesophagus has narrowed, while an area above this has become stretched or enlarged. The specialist will also be able to see whether the muscle contractions of the oesophagus (peristalsis) are working normally or not.

Gastrografin swallow

A Gastrografin swallow is similar to a barium swallow – you have to swallow a liquid which contains an X-ray contrast medium – this shows up on X-ray and shows the oesophagus, including the outline of the inside of the oesophagus. Gastrografin is often used when a barium meal can’t be used. Gastrografin is less irritating to the body if there is a leak from the oesophagus, such as from a tear.

Oesophageal Manometry

Another investigation that can be used in the diagnosis of achalasia is oesophageal manometry. In this test, a thin tube with pressure gauges along its surface is inserted through the mouth or nose into the oesophagus. As you swallow small sips of water, the instrument measures the pressure along your oesophagus.

In a person with achalasia, the test usually shows that the muscular contractions needed to pass food along the oesophagus are weak or missing, and that the lower oesophageal sphincter is not relaxing as it should after you swallow. The sphincter may also have higher than normal pressure.

Endoscopy (gastroscopy)

An endoscope (a flexible tube with a light and camera on the end) can be used to examine the oesophagus.

If you have achalasia, this may show that the oesophagus is wider than normal. It would also show if there were any obstructions in the oesophagus or stomach.

During the test, the specialist may take a sample of tissue (a biopsy) from your oesophagus or stomach to examine in the laboratory for any abnormalities.

Complications and risks of achalasia

Many people with achalasia delay going to the doctor and getting a diagnosis because their symptoms are not causing major discomfort. However, if you think you may have achalasia, it’s important that you seek medical advice and treatment, because doctors believe the condition may slightly increase the risk of cancer of the oesophagus.

Other complications of achalasia can arise because of undigested food being regurgitated during sleep. If the food is accidentally inhaled into the lungs, this can lead to pneumonia, an abscess of the lung, or damage to the bronchial tubes.

Achalasia can also lead to inflammation of the oesophagus (oesophagitis).

Treatment for achalasia

Achalasia is treated by a gastroenterologist, who deals with problems of the digestive tract.

While treatments can’t repair damaged nerves or restore normal contractions in the oesophagus, they can often improve the symptoms of achalasia. They do this by weakening the sphincter at the base of the oesophagus, so that food is able to pass through to the stomach.

Balloon dilation

Often one of the first approaches used to treat achalasia is dilation or stretching of the sphincter at the base of the oesophagus. This is done by putting a small balloon inside the sphincter and inflating it.

Unfortunately, there is a risk during this procedure that the oesophagus can rupture or tear. The dilation process may also need to be repeated, as it can stop having the desired effect after a while, and this further increases the risk of rupture.

Medications

There are no medicines in Australia to specifically treat achalasia, although sometimes medicines may be prescribed to help relax the lower oesophageal sphincter. These include nitrates (such as glyceryl trinitrate) and calcium channel blockers (such as nifedipine), which are also used to treat high blood pressure and angina.

While these medications may help relieve some of the symptoms of achalasia temporarily, they are not effective in all cases, and tend to stop working over time. They can also cause unwanted side effects such as headaches and low blood pressure. For these reasons, they are often only used for people who are unable to have other forms of treatment.

Botulinum toxin

Botulinum toxin (Botox) is a nerve toxin that is well-known for its ability to relax muscles, including those causing facial frown lines and wrinkles. When used in the treatment of achalasia, Botulinum toxin is injected directly into the lower oesophageal sphincter via an endoscope. Although the procedure is relatively safe, it only provides temporary relief (usually for 3 to 12 months) and its long-term effects are not yet known.

Surgery

Surgery can be done to decrease the pressure in the lower sphincter of the oesophagus, using a procedure called myotomy (or Heller myotomy). This type of surgery is generally reserved for cases where achalasia does not respond to treatment using balloon dilation. During the myotomy, the surgeon cuts the lower oesophageal sphincter muscle to release the tension. The surgery is done laparoscopically (using small abdominal incisions to pass a camera and surgical instruments through) and under a general anaesthetic.

Although the operation is successful in about 85 per cent of cases, up to 20 per cent of people develop a condition called gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD) after surgery, which causes acid in the stomach to rise into the oesophagus and can cause heartburn.

A new operation known as peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has recently been developed, but is still being tested for its effectiveness compared to standard treatments.